The cellarers range, c.1114

/Philip McAleer studies the west range of the cloisters, thought to have been the cellerers range where food and drink for the priory was stored in cool, sunken vaults.

Of the four sides of the cloister, the one that probably escapes a visitor's attention is the west one. It has also been largely ignored in the scholarly literature. The little that can be known about it has not been pulled together to form even a tentative picture. Yet, as we hope to show, the west range is not without significant features of interest, and even a partial picture of it helps to complete our understanding of the medieval cloister as a whole.

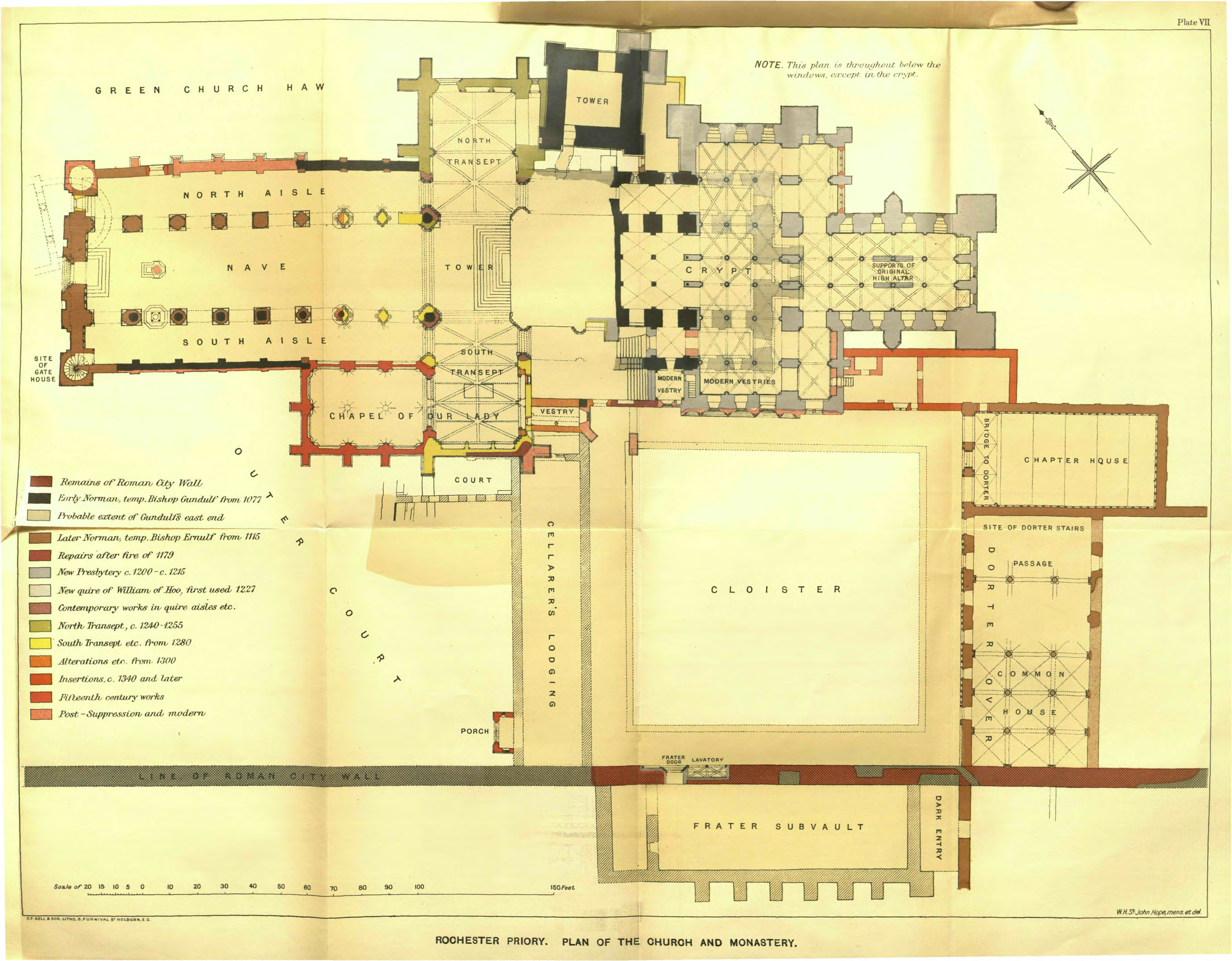

Of the first cloister and its surrounding buildings built by Bishop Gundulf (1076/7-1108) not a trace has ever been discovered. Although it has often been said that it occupied the usual position immediately south of the Romanesque nave, it is more likely that Gundulf's monastic buildings were on the site of the present cloister, unusually placed next to the east end of the church, due to the lay of the land. South of the nave, the ground level slopes up towards Boley Hill, while more level terrain was found on the east side of the transept, forming a more appropriate site for the large open flat area of the cloister garth, as well as for the buildings around it. The first documentary reference to the cloister is that which informs us that Bishop Ernulf (1114-1124) built the 'dormitory, chapter house and refectory', in other words, the buildings of the east and south ranges?. Is it significant that the west range was not mentioned? Or is its omission a reflection of the more mundane function of the structure of the west range - a vaulted substructure (an undercroft) to serve as a cellar for the monastic domestic goods and an upper floor to serve as the cellarer's 'lodging'*? Necessary, but less prestigious chambers than the meeting hall, sleeping quarters and dining hall of the monks. Because of the textual evidence, the fragmentary buildings still standing on the east side of the cloister have 'traditionally' been identified as Ernulf's work'. However, in recent decades, scholars of Romanesque sculpture have recognized that the motifs and style of the west front of the chapter house, and especially the tympanum portraying the sacrifice of Isaac by Abraham over the door to the former dormitory stair, could not date from the first quarter of the twelfth-century but were closer to the period of the 1140s. This date is not without significance, for the next reference to the cloister is one describing its destruction in a great fire of 1137, which apparently did cause such extensive damage that the monks temporarily had to seek accommodation elsewhere. It is therefore perfectly understandable that the surviving wall of the east range should be of the 1140s rather than 1114-248.

The south range, containing, perhaps, in addition to the refectory, a warming room and kitchen (at the west end), displays features of later date than the east range. Of particular importance are the obviously thirteenth-century portal and the monks lavatory, which are said to be the work of Prior Helias (1202-1222)°. Ernulf's refectory was rebuilt by Bishop Hamo of Hythe (1319-1352), in the 13301°.

Of the west range itself, a casual glance might yield the impression it was but an unexcavated bank (Fig. 1). A closer inspection reveals a buttressed retaining wall and a squarish room at the south end (now forming the Memorial Garden; Fig. 2). These elements are actually the last aspects of the cloisters to be revealed, for they were only excavated in 1938-911. What was disclosed seems at first rather meager, a low rubble wall with four large (brick) buttresses placed against its eastern face which were judged to be later insertions. Significantly, as will be seen, it lines up with the east wall of a small structure which occupies the angle between the south choir aisle wall and the east wall of the south arm of the major transept.

3D model of the cloister gate in the south-west corner of the west range, restored in 2022. Photography by Aerial Imaging South East.

Of more obvious interest was the discovery of Romanesque work at the south end of the range, for here were found three groups of shafts (Figs. 3, 4, 5). Each group originally consisted of three shafts placed in the angle of two walls, the middle shaft - the thickest

- positioned diagonally, the more slender flanking shafts placed in the angle between it and the wall'2. The bases of the shafts, above a low plinth, each consisted of a scotia over a torus which, in several cases, was elaborated by a narrow filletplaced between them or, in one case, by one or two grooves added above and below the scotia. The capitals were ofthe double scallop type or, for the larger shafts, of four scallops, several elaborated with elongated demi-pyramids, or arrow-like forms between the scallops (Fig. 3). The abaci were basically of a quirked hollow chamfer, in at least one case with several horizontal grooves on the vertical face. The shafts between capitals and bases, usually of four courses, measure twenty-seven inches in height.

From the abaci over the laterally placed shafts, sprang ashlar arches of which only the lowest courses remain (in two of the six possible locations). The diagonally-oriented axial shafts were obviously meant to relate to and support the diagonal ribs of a quadripartite vault, Unfortunately, none of the ribs remain to reveal their profile, and now only the rubble mass of the vault survives behind the position of their springing (Fig. 3). The arches springing from the lateral shafts would have formed the unmoulded wall ribs for the vault.

This end 'room' (if indeed it was a separate room, for the evidence of the north group of shafts is incomplete: were they in an angle formed by a cross wall or by a heavy pier which corresponded to a wide transverse arch?) would have formed part of the rib-vaulted undercroft of the cellarer's range which otherwise may have consisted of one long open space. The evidence of vaulting found here is of considerable importance, for it is the only testimony to the use of the ribbed vault at 'Rochester during the Romanesque period'4. As such, it is relatively sophisticated, including as it does wall ribs - or arches - and diagonally-placed shafts.

In the fourteenth-century, the vaulted chamber at the end of the south range was somehow converted into a vestibule when an entrance (known as the Bishop's Gateway) was constructed outside its west wall, at a level reflecting the then higher ground level', which is still lower than today's. It was at this time that the Romanesque ribbed vault may have been demolished, in order to allow descent into the area from the higher level on the west - unless only the western section of the vault was removed.

Following the purchase of the cloister area by the dean and chapter in 1558, the western range seems to have been adapted for use as prebendal houses, an adaptation which involved considerable rebuilding, no doubt at various periods.

The prebendal range oppears on several early maps of the cathedral precinct, most notably one of 1772 (Fig. 1)', and one made by Daniel Asher Alexander (1768-

Fig. 6 F. Baker, 'A Plan of the City of Rochester & c.' (from The History and Antiquities of Rochester and Its Environs [London 1772], frontispiece).

Fig. 7. D. A. Alexander, 1801, plan of cathedral precinct (British Library, K. Top.

17/8.1-2).

1846), dated March 1801 (Fig. 8)', In the former, the western range is shown as an

'L'-shaped structure, one arm of which paralleled the south facade of the major transept.

In the latter, it appears as a wide arm extending south from the south transept facade to which it is attached, with a much narrower wing extending to the west creating a narrow alley or court between it and the transept facade; the house was then occupied by one of the canons, Dr. Robert Foote (1798-1804), the cloister garth forming his garden". The appearance of part of the range, viewed from these gardens, is shown in a drawing of William Alexander (1767-1816) (Fig. 92, It reveals a 'picturesque' composition of a Tudor-style structure, with windows, entrances, and roofs on various levels, enlivened by two large oriel windows (each containing a 'Palladian' motif and several dormers of different sizes?. The north end of the range overlapped the east side of the major transept's south arm, the roof sloping steeply up to the sill of its east clerestory windows, and abutting the south choir aisle wall. It is with considerable surprise that among this welter of Tudor chaos one recognizes at the north end a completely different design. The narrow section of wall below the northern dormer is of a simple design, mostly solid and in one plane, with but a single, small, semicircularly-arched window in its upper zone.

Over it, is the curving line of a single larger arch, while double lines marking its sill and that of the springing of its arch are extended across the wall to its junction with the south choir aisle wall. It is clear that we have here the depiction of the only surviving window of the original Romanesque building of the range: a small window under a superordinate arch, with broad string-courses marking the level of its sill and impost, the lower string perhaps also indicating the level of abutment of the sloping roof which would have been over the west walk of the cloister.

This section of wall is equivalent to that which remains today as part of the projecting structure mentioned above, in the angle of the major transept arm and south choir aisle wall (Fig. 10). All sign of the Romanesque window has now, alas, disappeared. Early in the nineteenth-century, the prebendal house occupying the site of the west range was demolished22. (It was replaced by one positioned diagonally across the south-west corner of the cloister: it was this early nineteenth-century structure which was removed in 1938, allowing the discovery of the Romanesque chamber'). By 1816, only the Romanesque bay remained. It appears in an engraving of that date?*, in which one can just make out the trace of the two arches - the window head and the superordinate one.

This fragmentary structure was extensively restored in 1875 by G. G. Scott, at which time the diagonal angle buttress was added and, it would seem, both the south and east walls completely refaced?.

Inside this small tower-like space one finds no remaining Romanesque details26. Instead

- another surprise - in its south wall there are two tall arches separated by a polygonal pier with three Purbeck marble shafts and polygonal moulded stone capitals?7. The arches themselves are unmoulded, of two orders simply chamfered. These arches are different in style from anything else in the cathedral, especially the neighbouring choir aisle and south transept arm. They represent, perhaps, a partitioning off of the end bay of the west range to orient it towards a use associated with the adjacent spaces of the cathedral, rather than with the monastic activities. It may be asked if these tall arches originally, as they now appear to do, form niches which could have been fitted with wooden shelves to serve as a library or sacristy? A small portal, now only visible from the south arm of the major transept, with its sill thirty-three inches above the present floor level, that has been associated with the establishment in the fourteenth century (by 1322?) of an altar to the Virgin Mary in the transept arm, which henceforth served as the Lady chapel, formerly gave access to it28,

A small fragment of the interior decoration of the west range appears to survive in a

'cupboard' formed in the exterior face of the east wall of the south arm of the major

Fig. 8. W. Alexander, c. 1798, drawing of west range of cloister (British Museum, MS.

Add. 15.966).

transept. Advooden door

transept. A wooden door protects the jambs - only the south one is splayed - of a small rectangular window, long blocked up*". Jambs and blocking are painted with imitation masonry joints and red flowers, one placed in the middle of each ashlar block. The painting is probably rather late in date, possibly from the late thirteenth or early fourteenth century, as it is similar to the large area of painted ashlar on the wall above the canopy of the tomb, usually attributed to Bishop John of Bradfield (1278-1283), in the south choir aisle.

The evidence from the surviving remains at the south end, and Alexander's depiction of the north end, suggest the west range was constructed in the first quarter of the twelfth century, and therefore could well be the work of Ernulf. If a date can be suggested with some certainty, it is more difficult to reconstruct the plan or dimensions of the original range.

Part of this range was excavated again in 1983, when a porch was built outside the portal between the south choir aisle and the cloister'. The stepped foundation of the east wall was partly uncovered; it was over three feet (1.08m) thick at the top.

This same area had earlier been subject to extensive but partial excavation when J. T. Irvine was underpinning the east and south walls of the major transept arm. At that time (1872), he reported finding a wall running parallel to the south facade, which he thought was the north wall of Gundulf's chapter house. This discovery led Wm. H. St. J. Hope, with George Payne, to excavate yet again. A wall of barely three foot thickness, was uncovered thirteen feet from the transept facade; it extended westwards for a length of forty-seven feet (from the south-east corner of the transept arm) before being 'lost' in later brick walls (of a former prebendal house?). Built of Kentish rag, 'with some tufa', it was pierced by five semicircular arches of which two were blocked (the third and fourth).

Hope reported that the north face of the wall was rough and that the 'upper parts' (of the arches?) had been removed, while there were remains of plaster above the arches on the south face??. Although he thought the wall was too thin to have 'been carried up any height' or to have 'supported an upper floor', he described no architectural details which would date the wall.

The wall with five arches in it is difficult to explain, especially as Hope though it too thin to be very high (that is, no higher than the sill of the south transept facade windows?33. The number of arches and their width - four feet, with piers of three feet between them - suggest an arcade between two similar (interior?) spaces. Yet the plastered face suggests an interior space to the south, the rough northern face an exterior space between it and the transept face. The position of this wall seems to relate to the east-west wing which appears on the maps of 1772 and 1801 raises the possibility that, despite its being built of Kentish rag and tafa, it could be a post-Dissolution construction, associated with the domestic use of the range.

Hope reconstructed a total width for the range of only thirty feet - including the thickness of the walls (internal dimension about twenty-one feet)34, much narrower than the south range (over thirty feet internally$) or the east range (forty-one feet seven and one half inches internally36). The narrowness of the west range could be explained by the desire not to block the lower windows of the south wall of the transept: thus the west wall of the west range lies just a little west of the transept's east wall. However, this explanation only holds true for the existing south arm of the Gothic transept which does have windows at a low level. In the context of a 'normal' layout in the eleventh or twelfth century, in which the cloister and monastic buildings were located south of the nave, the end wall of the transept was usually abutted for its entire length by the east range of the cloister so that there could be no windows in the lower half of the wall. Thus, there would be no compelling reason in the Romanesque period for the west range (in place of an east range) not to abut the south end of the transept. In the specific case of Rochester, the west range may not have directly abutted the south wall of the Romanesque transept only because the entire cloister was shifted further to the east to avoid sloping ground: therefore, it only overlapped the south wall at its east end. The creation of a court or alley. rather than a covered passageway or slype, outside the south transept facade only makes sense in the presence of the existing fenestration pattern of the wall.

But was the west range orginally only thirty feet wide? According to D. Alexander's map, the north end of the west wall of the west range abutted the south wall of the transept somewhere about its middle - i.e., at about the location of the line of tufa quoins below the level of the thirteenth century windows (Fig. 7). This suggests that the west range could have been much wider - possibly as much as forty-five feet, including walls three to four feet thick. This dimension does not seem immoderate compared with that of the east range (external width fifty feet). However, the room at the north end is only approximately twenty-one feet square but the shape and function of structures in the south-west corner of the cloister is unknown.

W. Alexander's drawing of the east face of the range reveals the reason for the unequal length of the lancet windows of the south choir aisle (Fig. 8). When its south wall was carried west, it accommodated the slope of the roof over the Romanesque west range by placing the sill at a higher level than the windows to the east. Although it may be too much to say that the level of the clerestory of the south arm of the major transept was established by the ridge of the pitched roof of the west range, one can see from the drawing how the two were adjusted. The angle and height of the roof against the east face of the transept arm, as well as its continuation to the south beyond the end of the transept, also suggest a width for the range greater than Hope proposed. If the range was as narrow as he reconstructed, the apex of the pitched roof would have been lower and well east of the transept's east wall, creating a flow of water off the roof towards the transept. presumably the Tudor prebendal houses utilized the width of the earlier range so that the apex of their roof, in the line of the south-east angle of the transept arm, becomes another argument for a structure wider than 30 feet.

Finally, we may note that in all the plans, the southward extent of the prebendal houses of the west range did not include the 'Romanesque room' now visible at the extreme south end. This suggests that in some way the south end of the range differed from the remainder, and the buildings at this angle may have been adjusted in scale to the rising ground level at this corner of the cloister.

Although it has not been possible to establish the exact form and dimensions of the west range - which could only be achieved by proper excavation - we hope these remarks have put the small part of it still visible in a larger context".

I wish to express my appreciation to Mary R. Covert for allowing me to publish some material she uncovered in the course of her researches on the cathedral, in particular to works of D. A. Alexander, Wm. Alexander and S. A. Handley.

Notes

The destruction of the medieval cloister began soon after the Dissolution when the former monastic buildings were extensively remodelled to serve as one of Henry VIll's roval houses on the route to Canterbury or Dover. See The History of the King's Works, A. M. Colvin, gen. ed., IV. 1485-1660 (Part III), (London 1982), pp.234-7. From the accounts (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Rawlinson D.785, F. 1-118), it is clear that the east range was converted for use as the apartments of the king and queen (Catherine Howard), and the south range for use as a great hall; the latter was later altered to form one of two great chambers. There is no specific mention of the west or cellarer's range, although one can wonder where the great kitchen and 'Counsell' chamber were located.

For instance, Wm. H. St.J. Hope, 'The architectural history of the cathedral church and monastery of St. Andrew at Rochester', Arch. Cant., xxiii (1898), p.212 (or, as published separately, The Architectural History of the Cathedral Church and Monastery of St. Andrew at Rochester [London 1900], p. 19; as Part Il of Hope's study also appeared the same year, in Arch. Cant., xxiv, subsequent references will be given to both versions, because they have different pagination, as AC1898 for Part I, AC1900 for Part Il or L1900 for the complete work); G. H. Palmer, The Cathedral Church of Rochester: A Description of its Fabric and a Brief History of the Episcopal. See (Bell's Cathedral Series; London, 2nd edn, 1899), p.56; F. H.

Fairweather, 'Gundulf's cathedral and priory church of St. Andrew, Rochester: some critical remarks on the hitherto accepted plan', Archeological Journal, Ixxxvi (1929), pp. 197, 205.

British Library, Cotton MS. Nero D.Il. f. 109v[110v] (H. Wharton, Anglia Sacra, 2 vols [London 1691], I, p.342: 'Fecit etiam Dormitorium, Capitulum, Refectorium'); B.L., Cotton MS. Vespasian A.XXII, f. 88r(86r] (. Thorpe, Registrum Roffense [London 1769], p. 120: 'Ernulfus episcopus, pater noster post episcopum Gundulfum, fecit dormitorium, capitulum, refectorium'.).

Hope, op. cit., (AC1900)p.7 /(L1900)p. 142, supposed the east range of Gundulf's cloister was utilized as the west range of Ernulf's.

Hope, op. cit., (AC1900)pp.7, 35/(L1900)pp. 142, 170; Palmer, op. cit., pp.9-10, 56.

Perhaps the first to recognize its true date was J. Zarnecki, 'Regional Schools of English Sculpture in the Twelfth Century: the Southern School and the Herefordshire School' (Ph.D. dissertation, University of London, 1950), pp. 189- 90; see also G. Zarnecki, English Romanesque Sculture: 1066-1140 (London 1951), pp. 18, 23, 37, pl. 70; T. S. R. Boase, English Art, 1100-1216(Oxford 1953), pp.60-1. The later date of the decorative motifs has been confirmed during the recent cleaning: T. Tatton-Brown, 'The east range of the cloisters', Friends of Rochester Cathedral: Report for 1988, pp. 4-8.

B.L.. Cotton MS. Vespasian A.XXII, f. 29v[28v]; Gervase of Canterbury, Opera Historica, Wm. Stubbs, ed., 2 vols (Rolls Series, LXXIII: London 1879-80), I, p. 100

('Tertio nonas Junii combusta est ecclesia Sancti Andreae Roffensis et tota civitas cum officinis episcopi et monachorum'.).

The est range is described in detail by Hope, op. cit., (AC1900) pp.35-45/(L1900)pp. 170-80. B.L., Cotton MS. Vespasian A.XXII, f. 90r[89r] (Thorpe, Registrum Roffense,

p. 122: 'Lavatorium et hostium refectorii fieri fecit

...'.); Hope, op. cit.,

(AC1900)pp. 11, 30, 46/(L1900) pp. 146, 165, 181, pl. VI.

Cotton MS. Faustina B.V., ff. 56v(57v] (Wharton, Anglia Sacra, 1,

B 1. 37 1, 373: Refectorio et longo pristino noviter edicasouth

.; ... nunctamen

specialiter ad inchoandum novum Refectorium ...'). The south range is described in detail by Hope, op cit., (AC1900)pp.46-50/(L190-0)pp. 181-5; the warming room may have been at the south end of the east range (Hope, [AC1900] p.44/

[L1900] p. 179).

W. A. Forsyth, 'Rochester Cathedral: restoration of the Norman cloister', Friends of Rochester Cathedral: Fourth Annual Report (1939), pp.20-2, and pls. facing 15,

19.

The shafts - and angle of the walls - are best preserved at the south. The north-

east angle has vanished altogether, while of the rapidly crumbling north-west respond, only the angle-shaft's capital remains; there is no sign of the north cross wall.

For a list of diagonally-set ribs in early twelfth-century England see M. Thurlby, The Romanesque priory church of St. Michael at Ewenny, journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, xlvii/3 (1988), pp.291-2, n. 40.

The undercroft of the dormitory was vaulted with groin vaults: see Hope, op.cit., (AC1 900)pp. 43-4/IL 1900)pp. 178-9. Details of the undercroff of the refectory are not known: see Hope, (AC1900)p.48/(L1900)р.183.

Hope, op. cit, (AC1900)p.51/L 1900)p. 186 ('The porch at the opposite end no doubt opened into the passage or entry into the cloister from the outer court.);

Palmer, op. cit., p.58 ('(It) stands beside the road between the north (sic) main transept and the Prior's Gate, and opens towards the espicopal precinct).

See The History of the King's Works, IV, p. 236. George Broke, Lord Cobham, had been granted the house by Edward VI, and it was he who sold it to the dean and chapter.

[S. Denne and W. Shrubsole?] The History and Antiquities of Rochester and its Environs (London, 1772), frontispiece. A structure of the same shape appears in a plan in a notebook of Stephen Alex Hankey, 'De Conventu Roffensi', signed and dated on the last (unnumbered] page of the text, September 1843 (Rochester, Guildhall Museum); it is followed by a plan of the cloister area [ff. 41v-421, according to our reckoning. Both the key to the plan and the text [ff. 33-4, 37-8,

38-9, again our reckoning] identify the east-west wing (No. 11) as 'Heath's Parlour', and the north-south wing (No. 12) as the residence of the fourth prebend. He traced the origin of 'Heath's Parlour' to a lease of 1596 of part of the former cloister to one Philip Heath.

British Library, K. Top. 17/8.1-2. Alexander, an engineer, was surveyor to the London Docks, as well as to the Rochester Bridge Wardens.

On Alexander's plan, the main arm is identified as No. 6, the court or alley as No.

7. The former, according to the notes to the plan prepared by Thos. Dampier, was the house of Dr. Foote, 'old & ruinous - to be taken down completely. Dr. Foote held the fourth prebend (J. Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1541-1857, IlI.

Canterbury, Rochester and Winchester Dioceses, J. M. Horn, comp. [London

1974], p.66).

British Museum, MS. Add. 15.966, fol. d. Wm. Alexander was born - and died - in Maidstone.

This may be the structure, then in the possession of one John Heath, described in the Parliamentary Survey of 1649 (Medway Area Archives Office, DRc/Esp 1/2, ff.

54-5) as consisting of 'a Kitchyn, a Woodhouse, & Cellar and Three upper Roomes with a Garden butting upon the Library towards the East, and doth Conteyne by estimation one hundred foott in Length and fourtie foott in Breadth The date 1805 is suggested by M.A.A.O., DR/Emf 49, which seems to refer to this building. The range does not appear on the map which serves as the frontispiece to the second edition (1817) of The History and Antiquities of Rochester and its Environs.

See G. M. Livett, 'Medieval Rochester', Arch. Cant, xxi (1895), folding map, and Hope, op. cit., pl V. A photograph of this prebendal house appears in 13 Centuries of Goodwill: Friends of Rochester Cathedral, 604-1935 (1982), p. 16.

J. Storer, History and Antiquities of the Cathedral Churches of Great Britain, 4 vols (London 1814-19), IV, (Rochester] pl. 6.

1. T. Irvine, who actually supervised the work of restoration, directed by Scott, later wrote of the structure (M.A.A.O., Drc/Emf 77/133, p.5 (DRc/Emf 77/135 p.4]): 'In the heart of the wall an impost moulding of an arch or part of a string was discovered. It unfortunately could not be left open but was carefully left intact.

This space now serves as the storeroom for the cathedral gift shop. Formerly, after its restoration in 1875, it functioned as a vestry. Prior to that, according to Hankey, op. cit. [ff. 35-61, it had been 'degraded ... to a mere lumber room ...". It stands on the south half of the site of Hope's putative 'Gundulf's lesser tower' for which see Hope, op. cit., (AC 1898)pp.203, 210, 252, 264, 265, (AC1900)p.51/ (L1900)pp. 10, 17, 59, 71, 72, 186. The idea of a south tower, as a pendant to that on the north (the so-called Gundulf's tower), originated with Irvine: see Hope, (Ac1898)p.210/(L1900)p. 17

Hankey, op cit. [f. 36], mentioned 'a few low [sic] arches are still standing' in 'this apartment'. Hope, op. cit., (AC1900)p.51/(L1900)p. 186, did not mention them at all.

Hope, op. cit., (AC1898)pp.293-4, 297/(L1900)pp. 100-1, 104.

It was revealed in the restoration of 1875. Hope, op. cit., (AC1900)p.51/ (L1900)p.186.

D. Bacchus, 'Researches and discoveries in Kent: Rochester Cathedral, south door porch excavations', Archaeologia Cantiana, ci (1985), p.257(a), figs. 1 and 3 (section B-B).

M.A.A.O., DRc/Emf 77/133 (Notebook No. 2), p.4 (DRc/Emf 77/135, p.3):

Parallel nearly and about 00 feet from the gable wall of transept another exists whose N. side was seen. This certainly from its construction appeared to be Gundulph's workmanship. The top of a construction arch towards it(s) East end was seen/opened to view, but . . . little more than the direction and probable width was obtained . .. this would have much the appearance of possibly a North wall of a Chapter House of his time'.

Hope, op. cit., (AC1900)pp.51-2/(L1900)pp. 186-7, pl. VII. The site was identified as the Garden of Canon (George Edward] Jelf (1880-1907). The excavation was stopped by the 'peremptory order' of Dean Samuel Reynolds Hole (1887-1904).

For these reasons, Hope op. cit., (AC1900)pp.51, 52/(L1900)pp. 186, 187, decided it was unlikely a hall could have projected westwards from the range, or that a chapel (mentioned in 1425) associated with it could have been here (Thorpe, Custumale Roffense, p.571: 'capella sita in parte orientali majoris aule prioris et capituli ecclesie cathedralis Roffensis').

Hope, op. cit., pl. VII, according to the scale.

Hope, op. cit., ((AC1900)p.48/(L1900)p. 183: about thirty feet wide and at least 124 feet long.

Hope, op. cit., (AC1900)p.43/(L1900)p. 178: ninety-one feet in length by forty-one feet seven and one half inches in width; it was divided into three alleys by two rows of round(?) piers.

Unfortunately, these precious remnants of the west range (and Ernulf's period?) are fast disappearing behind thriving shrubbery whose vigor threatens their preservation. A rescue operation is needed to conserve these not so minor 'ruins

Glossary

Abacus A narrow rectangular, horizontal slab on top of a capital, beyond which it slightly projects.

Chamfer The flat-surfaced diagonal plane created by cutting off the corner or angle of a rectangular block.

Fillet A narrow flat-surface band or strip used as a moulding.

Quirk A V-shaped groove running lengthwise in a moulding or on an abacus.

Scotia A larger concave moulding, usually part of the base of a column or shaft where it appears between two forms mouldings.

Torus A large concave moulding, generally used to form the base of a column or shaft, above and below a scotia.

Dr. Philip McAleer teaches Architectural History in the Technical University of Nova Scotia. He is interested in Romanesque architecture, particularly west fronts in the British Isles, on which he completed his doctoral thesis for the Courtauld Institute in 1963. He is one of the foremost authorities on our cathedral, and is currently preparing a major contribution to a book by various authors on this subiect. His extensive article on the west front was published in last year's Friends Report.

Mary Covert has done a great deal of research into the fabric and the archives of Rochester cathedral, and has worked in collaboration both with Dr. McAleer and with Anneliese Arnold on various projects. She lives in the United States. It was she who discovered the 'Ringerike' stone in 1988. It was also she who contributed the article on the Cottingham papers in last year's report, which was unacknowledged. The Editor apologizes for this oversight.

Find out more

The duties of the cellarer’s doorkeeper in 1225 are recorded in Custumale Roffense. It is not known if the door referred to is that which survives on the south of the range or another.

Duties of the Cellarer's Doorkeeper, c.1235

The cellarer’s range formed the west range of the priory cloister and was were food, wine and other goods were stored in cool, sunken vaults.

EXPLORE

The Friends of Rochester Cathedral were founded to help finance the maintenance of the fabric and grounds. The Friends’ annual reports have become a trove of articles on the fabric and history of the cathedral.

Piecing together the thousands of architectural components and evidence from excavations and other sources informing the architectural history of the site.