Slaves and the Unfree in the Laws of Æthelberht

/Content Warning

This article contains discussion of topics THAT MAY BE INNAPROPRIATE FOR YOUNGER AUDIENCES.

Find out more about Safeguarding at Rochester Cathedral on our Safeguarding page

Slaves and the Unfree in the Laws of Æthelberht

November 04, 2021

Slavery at the turn of the sixth and seventh centuries, the period in which the laws of King Æthelberht of Kent are set, is not always easy to categorise. For over a century, for that part of Britain that came to be known as England, there had been conquest and subsequent settlement by Germanic tribes, and slavery was a significant part of the social structures that developed. As Textus Roffensis reveals, at this time there were, most certainly, unfree people who did not have the same status in the eyes of the law as did free persons: individuals who were essentially viewed as property – chattels – of their owners.

Where these people were drawn from at this time is less clear. It seems quite probable that the majority of slaves were captives through conquest and internecine warfare, whether indigenous Britons or those from outside one’s tribe or chiefdom (Pelteret 1999, p. 423). But there may also have been persons from within one’s group who were made slaves as an act of punishment, such as the penal slaves in the days of Ine, king of the West Saxons (reigned 688-722). However, in Æthelberht’s Kent there is no clear evidence about penal slavery, for his laws do not state what sanctions were imposed on those unable to pay fines for their unlawful acts (Pelteret 1995, p. 32 and n. 162).

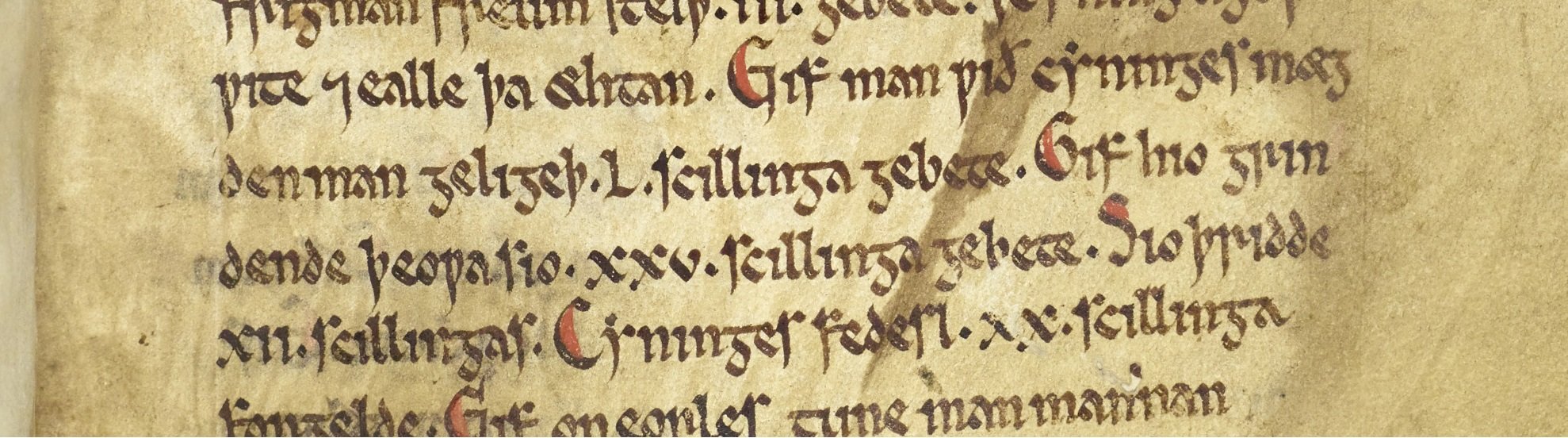

The first folio of Textus Roffensis, Æthelberht’s Code. The law code dates to circa 600 CE and is the earliest surviving law code in English.

Æthelberht’s Code does not make mention of the origins of slaves even when it directly refers to them – which it does by using the words þeowa (a female slave) and þeow (a male slave). We can nevertheless learn a few things about their legal status, in particular how unlawful acts committed against them or by them were to be handled. We can also learn something about persons who seem to be part-way between a slave and a freeman: the læt and the esne.

Women as slaves

The first occurrence of ‘slave’ in Æthelberht’s laws is in the context of unlawful sex with the king’s female slaves:

Gif man wiþ cyninges mægdenman geligeþ ·L· scillinga gebete.

If one lies with a king’s maiden, one should pay 50 shillings.

Gif hio grindende þeowa sio ·xxv· scillinga gebete.

Should she be a grinding slave [grindende þeowa], one should pay 25 shillings.

Sio þridde xii· scillingas.

Be [she] third[-class], 12 shillings.1

The Old English phrase geligeþ, ‘lies with’, is used euphemistically throughout Æthelberht’s laws to mean ‘has sex with’. Contextually, it is used to mean illicit, or unlawful, sex. By itself geligeþ does not connote rape, though rape of slaves should not be discounted here as a possible meaning. Later, the same word is used to refer to adultery, lying with the wife of another man, be he free or one known as an esne, an individual not fully free (more on this later).

It is unclear whether the ‘king’s maiden’ is a free-woman servant or a slave. She may correspond to the ‘cup-bearer’ [birele] found in two parallel clauses which most probably refer to a particular slave of both a nobleman and a ceorl, the lowest rank of freeman. In the latter case, the law is:

Gif wið ceorles birelan man geligeþ ·vi· scillingum gebete.

If one lies with a ceorl’s cupbearer [ceorles birelan], one should pay 6 shillings.

Aet þære oþere ðeowan ·L· scætta.

For the second-rank slave, 50 sceattas [=2½ shillings].

Aet þare þriddan ·xxx· scætta.

For the third-rank, 30 sceattas [=1½ shillings].

In the case of any female slave, owned by her master and hence coming under his legal protection, one having sex with her was treated legally as violating his property, and so compensation had to be paid to the owner. The amount was dependent not only on her relative status – whether she was a first, second, or third rank slave – but on the status of the man – king, noble, ceorl – who owned her, thus underscoring the subjugation of female slaves.

What types of work did female slaves do?

What exactly was a ‘grinding slave’? It appears to refer to a woman who prepared food for the household, in this case, specifically, the king’s household. Her position was a trusted one, since she was essentially handling the king’s food, and hence her status was above the third-rank female slave who may have carried out more menial tasks (Oliver, pp. 88-9).

This twelfth or thirteenth-century grinding stone discovered during excavations in the cloisters in the 1980s is perhaps something like that used by the grinding slaves of previous centuries.

The most obvious grinding in this context would be that of corn in preparing flour for making bread. It seems that the water mill may have arrived in England a number of decades after Æthelberht’s time (Oliver, p. 89; Blair, p. 248), so more manual forms of grinding were evidently in use.

This was arduous work, even if we probably shouldn’t imagine the king’s grinding slave using a saddle quern, where an upper stone is held between both hands and laboriously rubbed back and forth over the grain within a lower, hollow stone. It is more likely that she worked a variety of rotary quern called a pilstaff, a more advanced handmill in which a handle, attached to the upper stone, was rotated to create the grinding effect (Hagen, pp. 247-49). Still, this must have been back-breaking work.

The other occupation of female slaves mentioned in Æthelberht’s laws is the ‘cupbearer’, birele in Old English. The Dictionary of Old English suggests this may have meant more generally a ‘serving-maid’, not simply one who served drinks.

It is noteworthy that even a ceorl, the lowest rank of freeman, may potentially have had a cupbearer as a slave. I find this quite curious. Presumably the household was wealthy enough to support a non-family member as a dependent, a ‘loaf-eater’, and in return some of the domestic work that ordinarily would have fallen to the freewoman of the home was taken on by the slave-woman.

Sex-slave?

However, I wonder if in certain circumstances the birele was more than a domestic slave: could she have been, or have become, the sexual partner of the freeman? Perhaps, for example, if the ceorl was widowed, he may have taken a slave woman as a concubine rather than re-marry.

This is admittedly conjecture. But it should be observed that the specific role of cupbearer – serving drinks to honoured guests – is traditionally associated with the wife in more elite households.

Intriguingly, as Lisi Oliver notes, one of the duties of Queen Wealhtheow, in the famous Old English poem Beowulf, is to serve drinks to the heroes in the mead-hall of her husband, King Hrothgar. Moreover, her name, observes Oliver, ‘is a compound of wealh, ‘foreign’ and þēow, ‘slave’ (Oliver, p.88). Could the meaning of her name hint at Wealhtheow being a captured woman who rose to the status of queen? Could it reflect an early cultural tradition of slave-women transforming into wives of one sort or another?

We should note that Beowulf is found in a manuscript dating to around the turn of the first millennium, so not contemporaneous with the writing of Æthelberht’s laws. However, the poem’s origins may be significantly earlier, and its setting is certainly looking back to a time closer to Æthelberht’s, though in Scandinavia rather than England.

Men as slaves

Male slaves are referred to twice in Æthelberht’s Code, in the final two clauses:

Ðeowæs wegreaf se ·iii· scillingas.

For a slave’s [Ðeowæs] highway robbery, [compensation] shall be 3 shillings.

Gif þeow steleþ ·ii· gelde gebete.

If a slave [þeow] steals, there should be paid a 2-fold compensation.

These two clauses do not reveal a great deal of information about the lives of slaves. Highway robbery and theft are broadly dealt with earlier in the laws; these statements simply offer a more comprehensive view of the subject, explaining what is to be done in compensation terms when slaves rather than freemen are involved.

Oliver argues that the grammar of the Old English (there is ‘no agent’ in the first clause, and ‘no overt subject of the verb of recompense’ in the second) points to the master of the slave being the one who must pay the amounts stipulated, underscoring the slave’s status of being owned. Though we must note, too, Oliver observes, that in the later seventh-century laws of Wihtred (also uniquely surviving in Textus Roffensis) a slave could be fined 6 shillings for ‘offering to devils’, implying that a slave could own money or property and ‘be held responsible for his own fine’ (Oliver, p. 94).

Other unfree people

The life of people who seemed to be part-way between slave and free-person is also momentarily observed in the final clauses of Æthelberht’s laws. The læt, or ‘freed man’, appears as follows:

Gif læt ofslæhð þone selestan ·Lxxx· scill forgelde.

If one slays a freed man [læt] of the highest rank, one should pay 80 shillings.

Gif þane oþerne ofslæhð ·Lx· scillingum forgelde.

If one slays one of the second rank, one should pay 60 shillings.

Ðane þriddan ·xL· scillingum forgelden. Gif friman

If of the third rank, one should pay 40 shillings.

Here, then, we have a rank of persons (theoretically encompassing women, not just men) who were legally given a leod-geld (also called a wergild), a ‘man-price’ that had to be paid to kin as compensation. It wasn’t as high as a free person’s ‘man-price’, which is given as typically 100 shillings, and it was split into three levels according to the sub-classification, but this does nevertheless represent the legal recognition of these persons’ status above that of slave.

The Old English term læt, which only appears once in the entire corpus of Old English texts, has been interpreted as a former slave who is going through a process of manumission, though yet to obtain the status of a freeman. Oliver concludes that the term may be derived from an Old English verb meaning ‘release’ (Oliver, p. 91), making the individual, in effect, a released one.

She describes the tripartite division, evident in the clauses above, as probably representing ‘a class growing through three generations from a servile status towards the class of freemen, becoming fully free in the fourth generation’, and notes the existence of counterparts throughout medieval Europe (Oliver, p. 91).

David Pelteret offers a similar view, explaining that the ‘three classes signified the three generations required for the descendants of a freedman to acquire full freedom’. He also develops the argument that this system may have been brought to Kent via the Jutes (one of the settling Germanic tribes), but that it was not practiced by other invading tribal groups, eventually dying out once the ecclesiastical process of manumission, with immediate transformation from enslaved to freed status, became established by the Church (Pelteret 1995, pp. 295-96).

The other term used in Æthelberht’s laws to signify a status part-way between enslaved and free is esne. It appears as follows, just before the laws on robbery and theft by a slave:

Gif man mid esnes cwynan geligeþ be cwicum ceorle ·ii· gebete.

If one lies with a hired labourer’s [or ‘servant’s’; esnes] wife while the husband is alive, one should pay back 2-fold.

Gif esne oþerne ofslea unsynnigne, ealne weorðe forgelde.

If a hired labourer [or ‘servant’; esne] should slay another who is innocent, one should pay back the entire worth [of the victim].

Gif esnes eage ⁊ foot of weorðeþ aslagen, ealne weorðe hine forgelde.

If a servant’s [esnes] eye, or foot, is removed, one should pay to him the entire worth.

Gif man mannes esne gebindeþ ·vi· scll gebete.

If one binds another’s servant [esne], one should compensate with 6 shillings.

Pelteret explains that the word esne has a number of Indo-European roots, meaning ‘harvest time, summer’, and that by association it is linked with the labour carried out during the harvest (Pelteret 1995, p. 271). The esne, then, may be understood as someone temporarily bonded to a master as a labourer, perhaps particularly during harvesttime. Pelteret observes:

It seems unlikely that the esne was the same as a læt, since there is no hint of classes of esne. In the light of its etymological origin we may conclude that at this period the word most probably denoted a landless ceorl who hired himself out as a labourer. In a land-oriented society landless freemen would have been in a very weak position, so it is natural that they would have come under the protection of landed men. Their poor economic status would have reduced their rights and this explains why the law had to insist that in the event of the death of an esne his full value had to be paid, and that the same should apply for the loss of an eye or foot, vital for a labouring man. (Pelteret 1995, pp. 271-72).

Here, Pelteret understands, I think correctly, that the ‘another’ [oþerne] in the second clause, above, refers to another esne being killed. Oliver reaches the same conclusion; however, she offers amplification which helps us appreciate the lower social status of an esne. She explains that the use of ‘entire worth’, rather than referring to a wergild, indicates that the esne was only being ‘reckoned by his value as a labourer’ (my own emphasis). Moreover, if an esne was bound by someone, the dishonour was only compensated by a six shillings payment, compared to 20 shillings if a freeman is bound. As Oliver pertinently observes, ‘Although the offence is the same, the insult factor is less for a man who is already bound in another sense.’ (Oliver, p. 115).

The esne, then, was not a fully free person. Interestingly, Oliver directs our attention to one possible scenario which may have forced some free individuals to choose this lowly status, or even a lower one. Pointing to the context of theft, she remarks:

If the freeman is unable to pay the full amount [for the theft], he must render all that he does own. Logically, unless his kin supports him, he must now bind himself to another (as esne, ‘servant’ or slave) until he has the wherewithal to support himself. (Oliver, pp. 93-4).

Bibliography

Blair, John. Building Anglo-Saxon England (Princeton University Press, 2018).

Dictionary of Old English: A to I online, ed. Angus Cameron, Ashley Crandell Amos, Antonette diPaolo et al (Dictionary of Old English Project, 2018).

Hagan, Ann. Anglo-Saxon Food & Drink (Anglo-Saxon Books, 2006).

Oliver, Lisi. The Beginnings of English Law (University of Toronto Press, 2002).

Pelteret, David A. E. Slavery in Early Medieval England from the Reign of Alfred until the Twelfth Century (Boydell, 1995).

Pelteret, David A. E. ‘Slavery’, in The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England, ed. Michael Lapidge, John Blair, Simon Keynes and Donald Scragg (Blackwell, 1999).

Footnotes

1 All translations of Æthelberht’s Code are my own. You can see my full translation here.

2 The word ceorl is used here but not specifically in the sense of ‘freeman’, though it may help us understand that an esne was indeed a freeman who had fallen on hard times. In Old English texts, ceorl has a broader meaning than ‘freeman’, sometimes being used to simply mean ‘man’, at other times ‘husband’, and in legal contexts signifying ‘freeman’, and there are other nuances besides these; see Dictionary of Old English, ceorl.

Dr Christopher Monk

Related posts

These are the judgements which King Æthelberht set down in Augustine’s day. Translated from Old English by Christopher Monk.

Dr Christopher Monk explores the origins of Ethelbert’s law-code, foundational document of the Early English Laws portion of the ‘Rochester Book’.

Rochester Cathedral Foundation Charter, 604 CE*

Though a twelfth-century forgery, some boundary clauses within the document may be some of the earliest recorded place names in Old English.

The Laws of Hlothere and Eadric, c.673-c.686

These are the judgements which Hlothere and Eadric, kings of the Kentish people, set down.

These are the judgements of Wihtræd, king of the Kentish people. Translation from Old English of Textus Roffensis folios 5r-6v by Dr Christopher Monk.

Beast and interlace panel, C8th

Featuring the hindquarters of a four-legged beast, set beside an interlace panel, this fragment possibly from a tomb is the oldest sculpture yet discovered at the site.

Find out more about the most exceptional item in the Cathedral collections comprising over 170 texts from the 8th to the 14th centuries.

Explore the other legal codes in Textus from the 7th to the 12th centuries, many now available online for the first time.

Exploring the history of the Cathedral as contributed to by women, and items in the Cathedral collections revealing the lives and experiences of women in the past.

Most of the people in the past left little trace of their lives, often the poor or marginalised. They nevertheless helped shape the Cathedral and collections, sometimes the only tangible evidence of their lives, work and worship.